Interview Part 7: At the surgery

From my point of view the 1990s were tumultuous years, and with Teach-In 93 having been a broad success I kept my hand in with a small number of constructional projects and the occasional feature article. The most empowering development around this time was the arrival of my first PC in late 1992 (a 25MHz Ambra Hurdla 486 SX with 100MB disk and Windows 3.1, word-processing software (the lovely Lotus Ami Pro), then later a 2x CD ROM and finally a 14.4k then 56k modem). At this time, a wide variety of computer magazines were also on sale, these inch-thick weighty tomes reflecting the strong upsurge in personal home computing. There was much to see and learn for the computer enthusiast. Today, in 2014 I'm about to build a new PC that's nearly 150 times faster, for half the cost.

July 1993 cover featuring the Micro LabHaving got my GCSE part of Teach-In 93 out of the way, Keith Dye and Geoff MacDonald completed the “A” (Advanced) Level part of the series which featured the sophisticated Micro Lab. (See separate notes on the Micro Lab here.) Keith prepared a separate Micro Lab Technical Manual and managed all PCB, EPROM and PAL sales.

July 1993 cover featuring the Micro LabHaving got my GCSE part of Teach-In 93 out of the way, Keith Dye and Geoff MacDonald completed the “A” (Advanced) Level part of the series which featured the sophisticated Micro Lab. (See separate notes on the Micro Lab here.) Keith prepared a separate Micro Lab Technical Manual and managed all PCB, EPROM and PAL sales.

Due to the complexity of the design, and being at the mercy of industry supply lines, it was a miracle that the Micro Lab reached the amateur market but everything fell into place perfectly, thanks in no small part to Keith’s engineering expertise. I gathered together a kit of parts for my own Micro Lab – acting as a guinea pig – and mine worked first time with the LCD booting up successfully. It was used for photographic purposes and was seen on the cover of July 1993 Everyday with Practical Electronics.

There would be plenty of top quality material for 6502 enthusiasts to get their teeth into. Part 10 of Teach-In 93 contained the 6502 Instruction set and Geoff’s demo programs were introduced, which were stored in the Micro Lab monitor already. Part 11 included interfacing techniques which exploited the Micro Lab’s brilliant A/D and D/A IO. The final part showed how the Micro Lab could control lamps, stepper motors and external peripherals. It even played a tune (Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star).

It was very saddening that the full potential of the Teach-In Micro Lab was never reached. They had exciting plans for a relay board, a new power supply, a printer port and a robot buggy called Robo-Spot. Those developments were based on our experience of the popularity of the Mini Lab, but in the event the modest volumes of Micro Lab sales (despite the release of the Teach-In 7 book later) meant that the decision was taken to halt any further developments. A real shame.

Today, probably a PIC microcontroller and a few peripherals could perform more or less the same thing, but at the time the Micro Lab was a state of the art microprocessor training and development solution that did the magazine – and its readership – proud.

Keeping my hand in, my industry job in consumer product design introduced me to barcodes, and for light relief I wrote a small article explaining how they worked, hence Those Amazing Barcodes appeared in the August 1993 issue. (How EAN-13 Barcodes are calculated is shown in this PDF.) A toy called the Barcode Battler by Mattel was also reviewed in the July 1993 issue (featuring the Micro Lab). The idea was to swipe barcodes from consumer products and win “battles” by trumping an opponent’s barcode.

Doctor’s Surgery

With Teach-In out of the way, Editor Mike offered me Circuit Surgery – EPE’s column created by Mike Tooley which answered readers’ letters and queries. Mike Tooley was a hard act to follow but I enjoyed writing this column immensely to begin with, although (carefully not humblebragging) I was a bit apprehensive of my limits in electronics due to my lack of any electronics training. Hence I took great care to ensure that I was not “oversold” by the magazine nor did I want to bite off more than I could chew.

There was plenty of material to choose from in these mid 90’s pre-email days, when I would literally take a carrier bag full of mail to the post office and letters were sent all around the world (Wimborne provided airmail envelopes for this task). Life at the Surgery reflected the continued strong interest in discrete electronics at this time, along with a keenness to learn. The monthly column wrote itself really, as all I had to do was choose from a plethora of readers’ correspondence every month and send my copy off for publication.

However I eventually found that the page was treated more like a free design bureau, with readers sending outlandish requests or demanding that I design a bespoke circuit for them. Sometimes subscribers asserted “special rights” and demanded a 1:1 reply along with a free design consultancy. Or, having answered a question, they would come back wanting more. Circuit Surgery became unsustainable especially as I still had my day job to handle, and so in the latter 1990’s I introduced Ian Bell as a co-writer. Ian and I had worked at a local university for an industrial project (same one with Keith Dye, Teach-In 93’s co-writer) and he was immensely gifted as an electronics lecturer.

In due course Ian took over the Circuit Surgery column and I could finally hang up my guns. Ian’s scholarly work in electronics would take EPE readers and students where they needed to be, simulating circuitry on-screen and analysing formulae. EPE had not, until then, embraced these clear trends in circuit development and was still stuck at a hobbyist level. Ian helped introduce the new design tools heading our way and his work is widely appreciated to this day by readers all around the world.

Ingenuity’s Return

Out of Circuit Surgery I also relaunched Ingenuity Unlimited, readers’ own circuit ideas that hailed back to the start of Practical Electronics in November 1964. Talk about going full circle, as Ingenuity Unlimited kickstarted my own interest in electronics authoring as a schoolboy (Practical Electronics, December 1975), and here I was, at the helm of the very same column. Again the readership showed a lot of interest in submitting their ideas around this time and (unlike today) it was possible to publish an entire supplement of circuits, interest in circuit design was so strong.

My routine involved scanning readers’ letters and OCR’ing them, a neat trick in the mid 1990s, then getting a physical signature to claim originality, despite which a small number of fraudulent copied circuits still found their way into print. Sad to say, IU has all but petered out today because the readership has moved on to microcontroller design and seems to have lost all interest in discrete electronics itself. IU would today, if it were possible, contain page after page of PIC source codes instead.

More projects!

I was still interested in dabbling in project design and building, and I managed to churn out a small number of constructionals but I had much less free time and it was pretty hard going after all these years, this and a day job to hold down too. I usually built something that I had a personal need for.

Pond Heater Thermostat (EPE Jan 1994)Hence the January 1994 issue carried my Pond Heater Thermostat (article reprint and project notes), an LM3911-controlled outdoor weatherproof unit that turned on a floating pond heater to melt a circle of ice, which let my pond fish breathe (until a heron scoffed the lot).

Pond Heater Thermostat (EPE Jan 1994)Hence the January 1994 issue carried my Pond Heater Thermostat (article reprint and project notes), an LM3911-controlled outdoor weatherproof unit that turned on a floating pond heater to melt a circle of ice, which let my pond fish breathe (until a heron scoffed the lot).

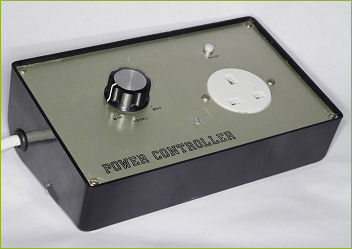

Later that year the November 1994 issue included another Power Controller, this time using an SL443 burst-firing chip to control larger heating elements (article reprint and project notes). I recall being on Usenet years later when a German designer asked for data on this chip. Remember there was no ‘web’ to speak of yet, so I posted a photocopy and got a nice picture postcard back from Munich in 1997, it’s still on my official noticeboard. To me, that’s what life was all about.

Burst-firing Power Controller (EPE November 1994)

Burst-firing Power Controller (EPE November 1994)

A Multi Purpose Thermostat was shown in March 1995 (article reprint and project notes) which also reflected my new interest in photography, as I took all the shots on a Minolta X700 SLR with 50mm macro lens and a very expensive Minolta 1200AF ring flash. The b/w shots I obtained from the film camera were really remarkable, perfectly and evenly lit, and the automatic ring flash produced some marvellous technical photographs.

A Multi Purpose Thermostat was shown in March 1995 (article reprint and project notes) which also reflected my new interest in photography, as I took all the shots on a Minolta X700 SLR with 50mm macro lens and a very expensive Minolta 1200AF ring flash. The b/w shots I obtained from the film camera were really remarkable, perfectly and evenly lit, and the automatic ring flash produced some marvellous technical photographs.

I did enjoy this phase (no pun meant) of mains-powered projects and they all shared the same style, trying to mount everything on a single board with minimum interwiring, making a sealed unit as far as possible.

My final traditional constructional project – now published nearly twenty years ago - would be the Windicator of EPE July 1995 (article reprint and project notes), using an LM3914 bargraph with a simple signal generator based on a d.c. motor. This prototype saw sterling service at home before EPE editor Mike acquired it, to show when the weather was windy enough to launch his dinghy. I recall calibrating it by sticking the motorised head through the sunroof of my car while pelting down country lanes, trying to read a voltmeter and compare against my speedo whilst keeping the car on the road at the same time. It worked well enough, thanks to the good quality d.c. motor supplied by Magenta. Again I took the photos, rather too many of them!

Ohm Sweet Ohm

Max Fidling and Piddles the Cat in Ohm Sweet Ohm (graphic by Colette Brownrigg 1994)At one point Mike (I think I was on a visit) said he was looking for a humorous column, and asked me for some ideas. The result was Ohm Sweet Ohm, a genteel column written by one “Max Fidling”. I struggled for a pseudonym so I looked in the phone book for inspiration. I’d guessed “Max Fiddling” would be scarcely credible, but ‘Fidling’ with one ‘D’ was in the phone book so that’s the name that stuck.

Max Fidling and Piddles the Cat in Ohm Sweet Ohm (graphic by Colette Brownrigg 1994)At one point Mike (I think I was on a visit) said he was looking for a humorous column, and asked me for some ideas. The result was Ohm Sweet Ohm, a genteel column written by one “Max Fidling”. I struggled for a pseudonym so I looked in the phone book for inspiration. I’d guessed “Max Fiddling” would be scarcely credible, but ‘Fidling’ with one ‘D’ was in the phone book so that’s the name that stuck.

The series featured the intrepid Max and his companion cat, Piddles. Some of this exploits were true (pretty much anyway – e.g. the bee-keeper’s honey separator motor controller), but sometimes I had to be in the right mood to write some spontaneous humour before a plot gradually fell into place. I would spend a merry day drafting some lightly-amusing story or other on my Ambra PC, as Max fiddled with his electronics in the shed, with Piddles the cat looking on.

One reader (a soldier in the Israeli army) Emailed – a real novelty then - to say that Ohm Sweet Ohm was the first column he turned to and he found it hilarious, whilst another filled in his EPE postal questionnaire (which I saw in the office) saying it was rubbish, a total waste of space and should be ditched immediately. Ohm Sweet Ohm generated some mirth amongst my family members if nothing else.

Colette Brownrigg, the EPE art tart, drew a cartoon each month (just been speaking to her). One of Colette’s graphics (a 1994 artwork) is hanging on my wall – Mike framed it for me for Christmas. In celebration of my friends Max and Piddles I framed a colour print on my office wall, the charming “Cat in a cottage window, blinking in the sun” by Ralph Hedley (1881). I still enjoy glimpsing at the moggy sunning himself on the windowsill near my shoulder. See the Ralph Hedley Archive for details of this highly talented 19th C. artist and wood carver.

After the Windicator, I had not entirely given up on hobby electronics though. As a final fling I produced a series “Build Your Own Projects” which reflected my enduring passion for the practical side of our hobby, benchwork, fabrication and assembly, still using my Dad’s old garage workbench like I’d always done since the 1970s (and still do to this day). The series ran as follows:

- Nov. 96 – essential tools (and some pretty poor photos!)

- Dec. 96 – soldering tutorials

- Jan. 97 – printed circuit board fabrication

- Feb. 97 – case work, marking out and metal bashing

- Mar. 97 – assembly and wiring up (by now my photography was much better!).

“BYOP” was a useful run of short articles that kept things trickling along with the magazine.

In closing...

The Windicator was the final traditional-style constructional project that I had published. For me, an electronics enthusiast from my 1970s schooldays to the present day, the little Windicator exemplifies what hobby electronics has been all about: having decent civil fun, being resourceful, challenging our minds, designing from scratch and puzzling out little problems (whether maths, physics, electronics or mechanical ones).

We test out ideas and prove them with some measurements, adapting the circuit on a breadboard here and there and prototyping it, then finalising the circuit before producing the printed circuit board – designing its artwork and jiggling components around for the best fit – often an absorbing challenge that nowadays a computer would handle. Then exposing, etching and drilling the p.c.b. before soldering the parts together and trying our hand at some engineering, metalworking or plastic fabrication, aiming for the best finish possible if we wanted to, but not worrying if it looks home-made.

Lastly, we power up a project for the very first time – the most satisfying aspect of the whole challenge, when the fruits of our endeavours finally reward us by bursting into life (we hope!). Sometimes things don't go quite to plan, so we face the added challenge and detective-work of faultfinding our projects.

Tomorrow’s hobbyist will probably be soldering much less, but will be computer CADding, simulating circuits on-screen, programming source codes, burning microcontrollers, surface-mount soldering (somehow), CNC milling and 3D printing objects as well. Not to mention, connecting sophisticated pre-fabricated modules together, data logging, remote-controlling them and uploading to the Cloud. There will be more “Makers” and fewer thoroughbred “Constructors” and less pure fabrication of the sort we’ve grown up with. A whole different set of tools will be theirs to command.

I enjoy writing English – it’s something that started to gel when I was a young boy in the 1960s – so I went further by making stories out of my work, writing up projects and sharing my ideas in print for fellow enthusiasts to hopefully enjoy. It’s been a great blast to search through the archives and dig out my electronics prototypes spanning some 35 years, all the way from my first Mains Delay Switch of Everyday Electronics, April 1978 to the final Windicator of 1995.

Hobby electronics has a habit of re-inventing itself and spawning new areas of interest. Perhaps a new past-time of vintage electronics will spring up for old time’s sake, and old EPE projects will be revisited by those who are disillusioned by the curse of modern micro-electronics. My prototypes will be restored to as-new glory if I get the time, and some of them will be used, or put away again for a future bout of nostalgia. I hope readers enjoy seeing them again and might even be tempted to have a go at building some of them. You can’t beat the smell of rosin flux, after all.

In the next part, I head towards the present time with constructional projects on the back burner. My career takes a swerve and nearly crashes altogether at one point, but the Internet arrives and grabs the steering wheel. Either embrace it or get run over, I thought...

Friday, October 31, 2014 at 10:11PM

Friday, October 31, 2014 at 10:11PM